David Brophy

At some point soon I hope to write up some notes from my experience looking around for photographs for my forthcoming book. Along the way I came across quite a few interesting bits and pieces, things that won’t make it into the book but seemed worth noting here at least. It turns out that the archive of the Royal Geographical Society in London has an excellent collection of photos from Xinjiang, and particularly from the Ili Valley region (catalogue here). These consist mostly of E. Delmar Morgan‘s photos from his trip in 1880, but include some later shots, which I would tentatively attribute to the British journalist and Labour politician M. Philips Price, who detoured into Xinjiang on his first trip through Russia.

In 1880, E. Delmar Morgan was travelling through Ili in the midst of the negotiations between the Qing and Russian Empires for the restitution of territory occupied by Russia in 1871. His photos depict Ili as a desolate region, showing that it still hadn’t recovered from the violence of the anti-Qing rebellion of the 1860s. One of the towns he visited was Samar, or Zharkent as it’s now known, which lies on the right bank of the Ili river. Samar was originally a Qing garrison town, and was more or less razed to the ground during the rebellion. It ended up in Russian territory after the Treaty of Saint Petersburg in 1881, and is now the centre of the Uyghur community of Kazakhstan.

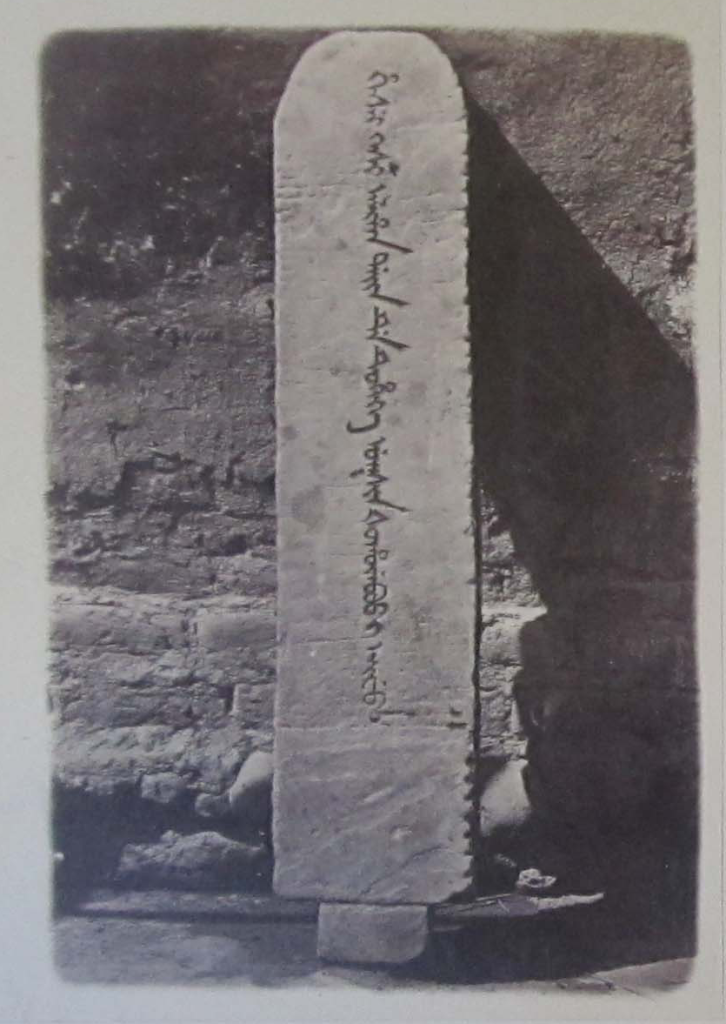

While passing through, Morgan snapped a couple of interesting grave steles, commemorating Qing soldiers (known as bannermen because they were organised into “banners”) who lost their lives during Jahangir Khoja‘s assault on Kashgar in 1826. Both of these bannermen belonged to the Manchu-speaking Sibe, a people who hail from from the north of Manchuria. The transplantation of the Sibe to the Ili valley took place in the 1760s, meaning that these men were probably third or fourth generation migrants. So, the steles commemorate Manchurian colonists, who fought and died to defend Qing-held Kashgar from Muslim rebels, and were buried in what’s now south-east Kazakhstan. They’re an interesting reminder of the scope of Qing imperium, from a part of the world where most such reminders have long been erased.

The first of the two is a pretty simple affair:

hesei kesi aliha dain de tuheke Uksin Šohūnboo i eifu

“[This is] the grave of Cavalryman Šohūnboo, who died in battle and received imperial grace by decree.”

I’m fairly confident this Šohūnboo can be identified with Shuo-hun-bao 碩渾保 in the Chinese sources, who is recorded as belonging to a Sibe cavalry squadron attached to the Solon Plain Yellow Banner in Ili (伊犁索倫營駐防正黃旗錫伯換防馬甲). This according to an official list of martyrs of that campaign, the Supplementary Edition of the Martyrs of the Temple of Loyalty (昭忠祠列傳續編), which can be read here (h/t Eric Schluessel).

The linguist Wilhelm Radloff, who first visited Samar/Zharkent twenty years before Morgan, says that the town was actually home to the Bordered Red Banner, while the Plain Yellow was based in Akkent, the next town to the east. It might be the case that Samar was the site of the local graveyard for all the surrounding settlements. But what were these Sibe doing registered to Solon banners in the first place? Radloff explains:

At the same time that the Schibö [i.e. Sibe] colonists became acclimatised in the Ili valley, and their numbers increased from year to year, those of the Solons were constantly diminishing, so that the Government, after about thirty years, found themselves compelled to import a large number of southern Schibös to fill up the thinned ranks of the Solon contingent. These were settled on the right bank of the river (Ili), and this became officially known as Solons because they belonged to the Solon contingent.[1]

The second inscription is slightly more elaborate. This one belongs to a man named Kicebu, who like Šohūnboo was a member of the Solon Plain Yellow Banner. It gets a little confusing here, as the published list of martyrs does include a certain Kicebu (奇車布), but says that he was part of a Sibe cavalry division attached to the Solon Bordered Red Banner. While this is the correct banner for Samar/Zharkent, it contradicts what the inscription says, so I can’t be entirely sure what’s going on.

Anyway, the inscription gives a lot more information than the first, including the fact that it was erected in 1845 – almost twenty years after Kicebu died. That strikes me as a very long time between his death and the gravestone going up. As is indicated by the Chinese at the top of the headstone – “by the grace of the emperor” 皇恩 – an imperial decree was required before you could set up a stele like this. Maybe someone will tell me that a twenty-year wait for official recognition of martyrdom status was normal for the Qing. Those familiar with the politics of martyrdom in the PRC today will know that claims for such status can take a very long time to get resolved. Or maybe this is just a reflection of the instability in Xinjiang throughout the Daoguang period (1820-1850).

Note: While I did obtain a high-res reproduction of this photo from the Royal Geographical Society, I don’t have permission to publish it, so I’m just providing the low-res snapshot here. Unfortunately it’s illegible, but even the high-res version is difficult to read in spots, so there are a couple of gaps in the transcription and translation.

Transcription

[Top] 皇恩

[1] ^ejen i kesi jalan halame beye tuhetele karulame faššarangge nimecuke ohode . hujufi gūnici . [2] gosin jurgan dorolon mergen tondo ni[…] niyalmai yabun ten . enteke jurgangga be ya (?) muteme tukiyececi [3] ombidere . emu mujilen i gurun jalin facuhūn ucuri tuksicuke nashūn de tušacibe mujin [4] bukdabuhakūngge dorolon i entehen .

[5] Solon aiman i gulu suwayan i Ukšin Kicebu doro eldengge i sunjaci aniya Kašigar i fudaraka [6] hūlha Janggir ubašafi hafan cooha tucibufi sunjaci aniya jorgon biyade dailame gaifi emu mujilen i [7] teng seme hūlhai dolo funturšame (?) juwan udu faidan afame [8] ^ujulaha jiyanggiyūn neneme beye wajiha . hūlhai f[…]ehengge geren ofi hoton hecen efujeme hibsu ejen i [9] gese afanara (?) jakade hūlhai baru afahai ningguci aniya ninggun biyai orin sunja de dain de tuheke . [10] turgunde amba cooha tucibufi a[gan] talkiyan i gese duin hoton be dasame toktobufi Janggir be jafafi [11] ^hesei gosire kesi isibume tondo jurgangga fayangga be selabuha .

uttu ofi jui Joringga se amaga [12] ejen i doro jurgan yabun be iletuleme . eldengge wehe de gingguleme folome arafi ilibuha .

[13] ^doro eldengge i orin sunjaci aniya bolori jakūn biyai sain inenggi Ukšin Kicebu goro hala i jui Ondongga, Joringga, Juwarumbu sei gingguleme folobuha .

Translation

By the grace of the emperor

Since selflessly striving for generation upon generation to recompense the emperor’s grace is a daunting task, upon humble reflection [we see that] compassion, righteousness, propriety, wisdom and loyalty constitute the height of human endeavour, and it seems to us appropriate to extoll these virtues. Single-minded devotion to the dynasty in a time of rebellion, without ever wavering in one’s resolve, is the utmost of propriety.

In the fifth year of the Daoguang reign, when the treacherous rebel Jahangir raised a revolt in Kashgar, officers and troops were sent out [to meet him]. In the twelfth month of the fifth year [January-February, 1826] they gave battle, and Cavalryman Kicebu of the Solon Plain Yellow Banner attacked with grim determination, driving more than ten rows [deep?] into the rebels. The commanding general gave up his life first. When the enemy’s […] became a throng, and they had destroyed the city walls and were attacking like a swarm of bees, he never ceased to assail the enemy, and on the twenty-fifth day of the sixth month of the sixth year [July 29, 1826] he fell on the battlefield. In response, the Imperial Army was dispatched, and like lightning they laid waste to the Four Cities and seized Jahangir. The emperor bestowed his merciful grace and commended [Kicebu’s] loyal and upright soul.

Thus in order to publicise his righteousness and propriety in the imperial cause, his son Joringga and others respectfully carved this stele and had it erected.

On the first day of the eighth month of the twenty-fifth year of the Daoguang reign [September 2, 1845], Cavalryman Kicebu’s sons Ondongga, Joringga, and Juwarumbu had this memorial inscribed.

Notes

[1] W. Radloff, A Narrative of the Insurrection in the Province of Ili in 1863-1866, trans. N. E[lias] (Calcutta: Printed at the Foreign Department Press, 1874), 3.