By Eric Schluessel

Researchers working on Xinjiang can face significant difficulty in gathering source material, especially when it comes time to visit the archives. Some young foreign scholars have seen success in the Xinjiang Regional Archives in Urumqi, but all of the other facilities in the region are difficult to access even for Chinese researchers. So, we have to get creative. Fortunately, Sweden is home to some of the world’s richest and by far the most accessible archives of materials specifically on Xinjiang. These are the East Turkestan Collection and the Mission Covenant Church of Sweden collections, both housed at the National Archives in Stockholm, and the Jarring Collection at Lund University. This introduction focuses on the two branches of the National Archives in Stockholm, while a further essay will discuss Lund.

All “reference codes” mentioned in this guide refer to items classified in Sweden’s national archival reference system. Note that this system does not only include items in the National Archive (SE/RA), but also in others. Be careful to note the exact location of what you are looking for. You can access this system through the Nationell ArkivDatabase (NAD).

A word about Swedish: I have personally found learning Swedish to be a very valuable tool in my work on Xinjiang history. Many of the Xinjiang materials in Stockholm are in Turki, Chinese, or English, but a majority of personal and organizational documents, including diaries, letters, and other intimate accounts, use Swedish. The Swedish Mission Church was active in Xinjiang from 1895 through 1938, and the members of that community, both Swedish and otherwise, experienced first-hand an especially tumultuous period in the region’s political history. Naturally, we are past privileging the experience of European travelers in exotic lands; however, I firmly believe that a critical scholar can make use of sources written from a variety of perspectives. Furthermore, it is rare to find such a rich archive of related materials on Xinjiang, rather than disparate and random documents, all in one place. In order to make use of the manuscripts, I took one year of university-level Swedish (which was supported by my half-remembered German) with an exceedingly good instructor and simultaneously took advantage of the printed literature produced by the missionaries in the antiquated Swedish of the early twentieth century. På obanade stigar, which presents short snapshots of Xinjiang life, made for especially good preparation.

Marieberg: the East Turkestan Collection and the missionaries’ personal papers

The majority of materials in Stockholm are housed at the main branch of the National Archive (Riksarkivet, pronounced Reeks-ahrsheevet) in the neighborhood of Marieberg in Westermalm. The Samuel Fränne collection of photographs, some of which one can see in Millward’s Eurasian Crossroads, and the personal collections of many missionaries are now being supplemented with newly-unearthed materials from the archives of the Swedish Mission Church.

About the Archive

The National Archive at Marieberg is a singularly pleasant and convenient facility. Upon entering, first get out your notebook, camera, and laptop, and stow the rest of your belongings in the free lockers to your left. Then, head down the stairs in front of you. You will not need identification, but bring it anyway. If you feel unsettled or confused by how easy this is, just ask the friendly guard or the helpful archivists what you should do.

When you get to the bottom of the stairs, those archivists will be at a long desk to your left. They speak English, Swedish, German, French, and even Chinese. Tell them that you are here to use the East Turkestan collection (Östturkistan sammlingen) or the materials from the Mission Covenant Church of Sweden (Svenska Missionsförbundet). The archivists are quite familiar with both collections, which seem to have a special place in the National Archives. Fill in the carbon paper slips at the desk with your name, the date, the number of the precise archive carton you will need, and your table number. If you are using East Turkestan materials, you will need to sit in one of the front-row seats in the reading room. Fill out one form for each carton, even though it might take a while. In order to ensure that you make the best use of your time, I recommend informing the archivists which volumes you would like by e-mail a week in advance. However, the longest I have waited for documents was a mere 45 minutes.

The documents will be delivered to your table in the reading room. You may want to wait outside, however, as sitting at an empty desk seems to make the archivists nervous. Some ground rules: You can have a maximum of five cartons at your desk at one time. Photography is allowed for academic and personal use, but make sure to ask first! If you plan to take photos, you will need to put a blue sign on your desk that reads “Foto tillstånd.” (These signs are sitting on the long archivists’ desk outside of the reading room where you fill out the request forms. Ask, and then take one in with you.) Laptops, remarkably, are permitted in the reading room. There is an office just off the reading room that will photocopy things for you, but at a price and only for cash or money order.

You get to the Marieberg archive by bus (there is no convenient T-Bana stop, though you could conceivably walk from Thoridsplan). Many routes go there, though I often took the #1 from outside Fridhemsplan T-Bana. Get off the bus at Västerbroplan. This may put you on Rålambsvägen, in which case you must follow the road west, make a left onto Gjörwellsgatan, and then a left on Fyrverkarbacken, which goes all the way up the hill. The Archive is at the top. If you are coming from the south, then the bus may also drop you right by the bridge over the river. In this case, there is a set of stone steps on the west side of the road that will take you right to the building. Lunch is available down at the bottom of the hill at a number of stands and restaurants. The Archive’s “cafeteria” has a pretty good vending machine.

The Documents Themselves

Let’s start with the Samuel Fränne collection. (Ref. Code SE/RA/720860) The collection consists of several cartons of cardboard sheets upon which are mounted photographs, documents, and short descriptive texts. Jarring’s index is included. Fränne indeed collected a great number of photographs of people and places surrounding the Mission, neatly categorized by topic, but the value of his work transcends the images. He supplemented each section with text – in Swedish – based on Mission documents and interviews with members of the community, so the collection forms a kind of illustrated encyclopedia. It’s a good place to start, and it might inspire new projects.

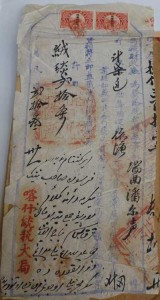

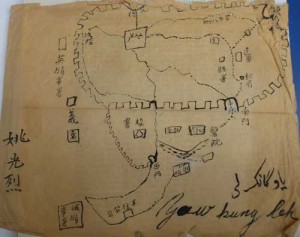

The personal archives of Mission members can be found in the Church archive. (Ref. Code: SE/RA/730284) The items in this collection are open for research use. This archive contains 268 subfolders and counting, only some of which pertain to Church member who were in Xinjiang, so it is best to look it up online and find out what you need ahead of time. The collections contain much more than just personal letters; rather, they bring together a range of materials from individuals’ lives in Xinjiang. Let’s take Rachel Wingate’s personal archive as an example (Ref. Code: SE/RA/730284/240): It contains two cartons, 1 and 2, which contain her personal documents and correspondence, respectively. The correspondence in carton 2 is just that, letters in various languages. Carton 1, however, contains a miscellany of Wingate’s own notebooks and school papers from her students. Gustaf Ahlbert’s archive (Reference code: SE/RA/730284/226) includes a book collection, and Gustaf Raquette’s (Reference code: SE/RA/730284/39) has many of his linguistic notes. One could conceivably make a whole project out of the missionaries’ notebooks, which track their progress in learning Eastern Turki.

Riksarkivet Marieberg

Fyrverkarbacken 13, Marieberg, Stockholm

Tel.: 010-476 71 44

E-mail: riksarkivet@riksarkivet.se

Hours:

Reference Desk: Mon-Fri 9.00-16.00

Reading Room: Mon-Wed 8.15-18.45, Thurs-Fri 8.15-16.15, Sat 9.00-13.30

Copy service: Mon-Fri 10.00-12.00 and 13.00-15.00

Arninge: the Mission Church archives

The Arninge branch of the National Archives is more difficult to access, but it could be even more valuable for the right researcher. While the personal documents of the missionaries can be found in Marieberg, the Arninge branch, which acts as a depository for the records of several churches in Sweden, holds the archives of the Mission Church itself. (Ref. Code: SE/RA/730284/261) The financial records of the East Turkestan mission, for example, are available for perusal – these include account books of various kinds, listing costs and expenditures in different currencies for periods in the 1900s, 1920s, and 1930s. An economic historian interested in the price of commodities and currency exchange rates might find these very interesting.

Some of these Mission records at Arninge, however, have been placed under “secrecy” until the year 2111 in order to protect the privacy and safety of those mentioned therein and their families. In order to request access, one must contact the Church itself. Check the collection online first to see if the subfolder you want is “secret” (sekretess).

To get to Arninge, take bus #629 from the Mörby Centrum T-Bana stop to Måttbandsvägen. This will take about 30 minutes. American researchers may feel uneasy at how far from Stockholm the bus travels. Indeed, the archives are in a small and otherwise unwelcoming industrial and commercial park. Cross the road and venture one block back – you will see a glass-and-concrete building with the Riksarkivet logo.

The same procedure applies as above. Make sure you ask at the desk about cameras and laptops.

Riksarkivet Arninge

Mätslingan 17, Täby

010-476 72 50

riksarkivet@riksarkivet.se

Hours:

Reference Desk: Mon-Fri 9.00-16.00

Reading Room: Mon-Wed 8.15-18.45, Thurs-Fri 8.15-16.15, Sat 9.00-13.30

Copy service: Mon-Fri 10.00-12.00 and 13.00-15.00

(Note: The above is based on two visits to the Riksarkivet in June 2011 and May 2012. In May 2012, I was told that the Archive would soon implement certain organizational changes, which could compromise the accuracy of some of this information.)